For Asian Americans, what does it take to confront autism?

Children at the Philadelphia Asian Family Health Resource practice social skills through origami frog races. Photo courtesy: Christina Lam

When Kevin Chang was first diagnosed with autism nearly 15 years ago in California, his grandmother thought it was her fault.

“She was blaming herself because (she thought) the reason why he’s speech delayed is that because she barely spoke English,” his father, Wonkoo Chang, said.

Like Kevin’s grandmother, many Asian families are mired by shame, language barriers and limited community resources, say advocates and families of children with autism. As a result, they’re less likely to get their children diagnosed or find and receive long term treatment.

“If you have a child with autism, then your family is culturally shamed because your family is not a good gene pool, or the parents did something wrong,” said Dr. Young Shin Kim, an autism researcher at Yale University. “There’s a lot of stigma.”

And local institutions and support networks that exist to help these individuals can sometimes let these vulnerable families slip through the cracks, as they struggle to provide the language and educational resources.

“Looking at the policies and the services conceived, they’re designed by abled people,” said Anna Perng, a Taiwanese-American mother in Philadelphia whose 4-year-old and 6-year old sons both have autism. “And when you add race and class, you’re starting to look at, ‘Who does this work for?’”

Autism By the Numbers

Graphic: Alexandra Yoon-Hendricks

Autism, or the autism spectrum disorder, refers to a range of conditions affecting social skills, behaviors, speech and nonverbal communication.

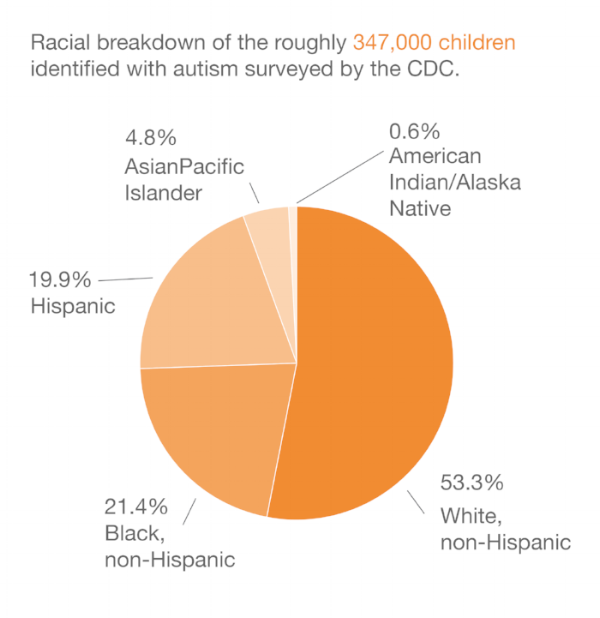

More than 3.5 million Americans are estimated to be living with the disorder, with Asians and Pacific Islanders representing a small but significant share of them.

Autism is identified more frequently in white children than in other racial groups — a trend that can sometimes create the perception of autism being a disease associated with only white individuals. And neither the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention nor the National Institutes of Health maintain comprehensive ethnic breakdowns of individuals living with autism in the United States.

Asians comprised about 5 percent of the roughly 347,000 children studied in a 2016 CDC report. That amounts to about one in 88 Asian and Pacific Islander children in the United States identified with autism spectrum disorder, which is comparable to the prevalence rates of Black and Hispanic children.

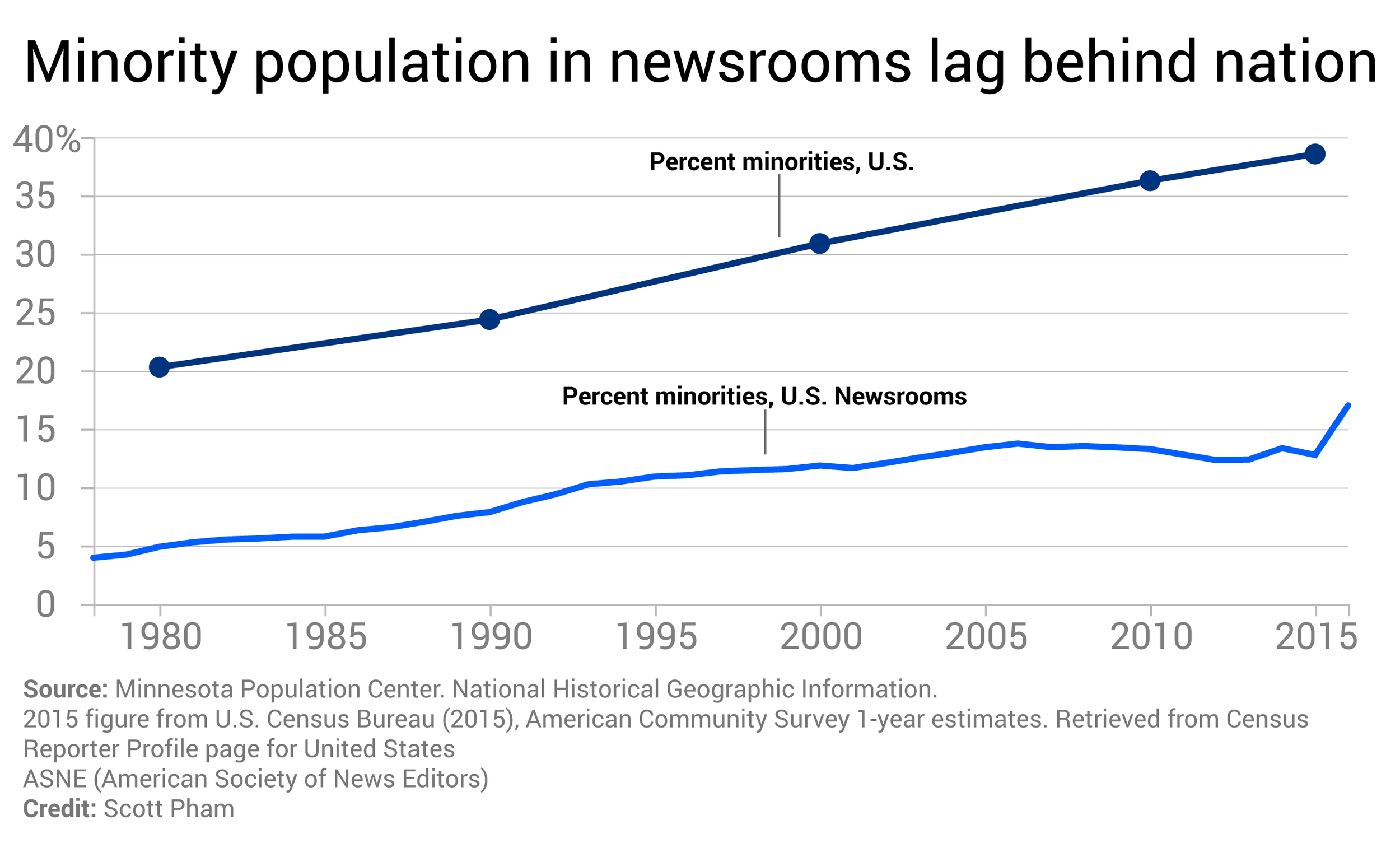

Efforts have been made to investigate delays in diagnoses and services for ethnic groups such as Blacks and Hispanics. But the challenges of Asian families continue to go underreported, in large part because families do not or cannot volunteer for research studies that require open disclosure or include complicated jargon, said Philadelphia-based clinical social worker Karen Krivit.

Graphic: Alexandra Yoon-Hendricks

"Nothing to be proud of"

In Asian communities, families sometimes hide the fact that a family member has a disability, whether it is developmental conditions like autism or other mental disorders, said Peter Wong, research director at the Asians and Pacific Islanders with Disabilities of California.

Revealing a mental disorder could jeopardize not only the child’s future, but also the family’s reputation, he said. Myths run rampant in the community, Krivit said. She added that some families may believe that a child with autism serves as an indicator that the family is being punished for a past wrong.

While conducting a study of autism prevalence in South Korea, Kim received an angry call from a participant’s mother, who complained that her son’s diagnosis caused her daughter’s boyfriend to break up with her.

“Her son was diagnosed with autism,” the Yale researcher said, “but her daughter’s boyfriend said, ‘I cannot date you or marry you because you’re genetically flawed.’”

Chang and his wife, Johnna Cho, still encounter similar cultural hurdles in the Los Angeles-area. Chang freely shares the family’s experience, but he said family members urge him to remain silent.

“Why are you telling people that he has autism?” Chang recalled them saying. “There’s nothing to be proud about that.”

To which Chang replied: “It has nothing to do about pride or being ashamed.”

The Road to Diagnosis

Initially, Chang and Cho sought out their family doctor to understand why Kevin threw tantrums, but their pediatrician reassured them that nothing was wrong with their son.

“Our pediatrician said, ‘I wouldn’t worry about it’,” Cho said.

Cho took her pediatrician's word for it, she explained. But as Kevin’s tantrums continued, she and Chang reached out for an official diagnosis nearly a year later.

Late or incorrect diagnoses can make it harder for parents and therapists to help children learn behavioral or communication skills.

In Philadelphia, the largest group of children getting late diagnoses are Asian immigrants, according to Krivit, who helps oversee the city’s system of about 8,000 special needs children.

“These are kids who could’ve been getting services at age two getting first diagnosed at age five or six,” Krivit said.

Dr. Naveen Mehrota, founder of New Jersey-based non-profit Shri Krishna Nidhi, remembers when he advised a family with an infant to seek further diagnosis for the child’s mental development. Instead, the family transferred out of Dr. Mehrota’s clinic and sought further advice from another pediatrician, who said the child’s development was fine.

Two years later, the parents discovered a large tumor in the child’s brain that was affecting the child’s development.

“The moral of the story is that we tell the parents something they don’t want to hear…especially people in our community,” Mehrota said “They want that perfect child who goes to Harvard.”

Lost in Translation

For many Asian families, particularly recent immigrants, even talking about autism spectrum disorders can be challenging, Wong said. Common terms in the world of autism such as “gross-motor planning,” a term used to describe large motor movements that a child with autism may have, could be a translation nightmare for an interpreter using an online service on the fly, Perng said.

Not every agency has the ability to provide interpreters during appointments, therapy or in-home visitations, and other language barriers can leave room for misinformation. The lack of API professionals in social work doesn’t help, according to San Francisco-based former speech therapist Dr. Betty Yu.

“Families may begin doing certain things that are not evidence based, spending a lot of time and money on something that’s a quick sell,” Krivit said. “Like, ‘If you use this nutritional formula … or go to this kind of therapy program, then your child will be cured.’”

Asian parents have a difficult time navigating health care and school systems in order to find resources for their children, according to Mei Ye, parent of a 15-year-old child with autism and outreach coordinator for the Chinese Parent Association for the Disabled in the Los Angeles area. She said that due to bureaucracy, she and other parents have gone back and forth between the two systems, frustrated. “It’s like a circle,” Ye said.

Mei Ye’s son, Laker, throwing a frisbee at the Los Angeles Chinese Parent Association for the Disabled center. Photo courtesy: Chinese Parent Association for the Disabled

Asians in particular have a problem speaking up for additional services for family members with disabilities compared to whites, according to Barbara Wheeler, the associate professor for the University of Southern California's University Centers for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities.

“They won’t necessarily say no because that’s an insult and a challenge to authority, and the authority is the regional center,” Wheeler said. “Even though they would like to say, ‘I’m not comfortable with this.’”

Parents need to be vocal advocates for their children and accept that autism is not something to be ashamed of, says Jean Lin, a mother of a six-year-old son with autism.

The southern California resident started volunteering in her son’s classroom and learning about current health policies after becoming frustrated by the quality of education and health care her son was receiving.

“We don’t talk as much as other cultures. We’re less open about it,” said Lin, who is a member of Chinese Parents Association for the Disabled. “Maybe in Asian culture we sometimes say more positive things and disability is not positive.”

Finding Help in Strangers

Some immigrant Asian families also fear that seeking higher quality care available in the United States may put them at risk for deportation, Krivit said.

Most special needs programs will never ask a family about their immigration status. But to provide a welcoming and inclusive community, support groups — many formed through parent volunteers — have stepped up to provide services to immigrants, no questions asked.

In fall 2015, Perng, with a group of parents and local resource centers, helped create Philadelphia Asian Family Health Resource, after medical officials expressed concerns that only one out of 10 Asian families were receiving referred autism-related services, Krivit said.

Since then, the largely volunteer organization hosts monthly workshops for parents and activities for their children, Krivit said. Translators are regularly present and equipped to translate complicated subjects such as immigration legalese and special needs education resources.

“There isn’t another workshop quite like this in the country right now,” said Krivit, who estimates the gatherings bring together anywhere from 30 to 50 families.

Yet, if parents are not ready for face-to-face support, they can turn to social media. With the prevalence of smartphones, community groups have utilized messaging apps so families can still be engaged in the community while privately receiving information about workshops, deadlines or education plans.

In New Jersey, the Shri Krishna Nidhi organization created a private WhatsApp group chat that has more than 50 members within the New Jersey community. Within the group chat, parents can better understand their child’s condition in a safe and inclusive space.

“You can communicate anonymously on this group, which then empowers the parents to talk about their issues without being judged,” Mehrota said.

And in Pennsylvania, the Philadelphia Asian Family Health Resource runs a WeChat group for about 30 Mandarin-speaking families in the area in collaboration with the city’s special needs services.

Some parents will call Mandy Lin, one of the coordinators, in the middle of the night, asking questions or seeking advice.

“Anytime they need me and I have time to answer a phone call, I’ll do it anytime,” said Lin, who is the mother of a 5-year-old son with autism. “Sometimes they need help and they can’t wait.”

Screenshot of WeChat conversation where group members are asked to fill out an online survey about topics most important to the parents to be discussed in future workshops. Photo courtesy: Mandy Lin

The Road Ahead

Wonkoo Chang and Johnna Cho with their son, Kevin, who played a clarinet solo for a fundraiser hosted by the Korean American Special Education Center in recognition of World Autism Awareness Day. Photo courtesy: Johnna Cho

Although Asian families face difficulties in finding resources and overcoming the shame and embarrassment associated of autism, experts argue that with adequate support and appropriate management, families and their children can live fulfilling, purposeful lives.

Nearly 17 years later, Kevin Chang, the boy with autism from Los Angeles, is among the success stories.

“I want to become a math teacher,” Kevin now a 19-year-old math major at the California State University, Fullerton said. “I guess throughout my experiences, like having to figure out my autism and disabilities, I want to help other kids with disabilities.”

Cho and Chang are proud of Kevin’s resilience and his unwavering optimism.

“It’s not something that gets cured,” Cho said. “It’s not like you can take the autism away, but you can help them have the tools that they need in order to live their life.”

Cho and Chang know the future still remains uncertain.

“There is still ... a lot of employment challenges, a lot of people don’t understand autism and they don’t understand people with autism,” Cho acknowledged.

But in the meantime, the family is taking things day by day.